- Home

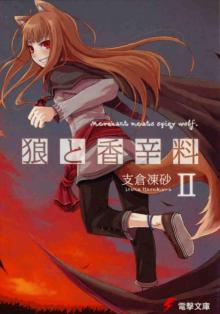

- Isuna Hasekura

Side Colors II Page 3

Side Colors II Read online

Page 3

He couldn’t discount the possibility, so after participating in the feast a bit longer so as not to offend his hosts, Lawrence, too, returned to their accommodations.

The third day of a winter’s journey often decided whether one’s body would accustom itself to the rigors of travel, and even veteran travelers could find their strength failing if they weren’t careful.

And Holo had already felt poorly several times.

Even the wisewolf who dwelled in the wheat was not immune to exhaustion.

Lawrence quietly opened the door to the building he was led to; inside it was dark and quiet.

He took a tallow lamp and slowly entered, and found that storage boxes had been arranged to form a makeshift bed in the center of the room on the earthen floor. The villagers themselves slept on straw spread upon the floor, so this was special treatment for honored guests.

What he could not guess at was why they had prepared only a single bed. Did they suppose they were being considerate?

In any case, Lawrence regarded Holo, who was already curled up in a blanket. “Are you all right?”

If she was asleep, that was fine.

After a few moments without a reply, Lawrence concluded that she was.

If she awoke the next day and was still feeling unwell, Lawrence would offer the villagers some money and stay a bit longer.

Having decided as much, Lawrence extinguished the lamp and curled up on the straw of the bed, pulling the thin linen blanket over himself.

He was careful not to wake Holo and seemed to have been successful.

Though merely straw, this bed was far more comfortable than the bed of his wagon. All he could see was the ceiling and its joists and what moonlight streamed through the small hole in the roof that was there to let smoke out from the hearth.

Lawrence closed his eyes and considered the village’s situation.

It held thirty or forty people. Nearby there were forests and springs, and fruit, fish, and wild honey were all surely abundant. It sported fine pasturing, too. Excepting the relative rockiness of the land, it seemed quite fertile.

If the abbey were completed, it would easily support a hundred people.

As long as no other merchant had already marked the place as his own, it seemed possible that Lawrence would be able to monopolize its trade. During the feast, he had spoken with the villagers; he had talked to them about trading for iron tools, cattle, and horses.

When a nobleman donated a remote parcel of land for the construction of an abbey, it often happened that they or someone close to them was nearing death. The plans were rushed, construction proceeding without important details having first been decided. And it was not necessarily true that the nobleman even lived near the land being donated.

Since deeds to lands were recorded on paper, they traveled like so many dandelion seeds blown on the wind. It was not unusual for land to be turned over to someone the nobleman had never met and barely knew of. The beggar’s patchwork of land division that resulted from such situations was the seed of many a dispute.

Thus it was common for neighboring communities to avoid contact with newly settled occupants, fearing they’d be drawn into such conflict. This village seemed to be typical of such situations, and evidently the merchants of nearby towns and villages were reluctant to do business with it. The village elder had said the young man taking the beer and chicken to the side of the lonely road where Lawrence had found them had been a last-ditch effort.

For Lawrence, the timing could not have been more fortunate. For the village, he was like a messenger from God.

It was only understandable that his face would redden with pleasure despite not having too much to drink. An opportunity he’d often dreamt of during his lonely travels was now right before his eyes.

So just how much profit would it bring him?

As the night grew darker, his mind brightened. The notion of his prospects here was a stronger liquor than any ale he’d been served, and—

He felt Holo shift in the bed, and then she spoke up with a sigh. “Honestly, you are a hopeless male.”

“Hmm, so you were awake, eh?”

“How could I sleep with the sound of you grinning away like that?”

Lawrence couldn’t help but touch his face to check.

“I left the feast in such a state, and you just kept grinning away, not a care in the world…”

Now that she had said as much herself, it was clear she had intentionally left early.

But Lawrence sensed that if he pointed it out he’d only earn her ire, so he chose his words carefully. “Your voice seems so cheerful now—I can’t tell you how relieved that makes me.”

Holo’s tail shifted beneath the blanket they shared. But Holo herself, who could tell when a person was lying, grabbed Lawrence’s cheek and bared her fangs. “Fool.”

She would’ve been angry no matter what his answer had been, but he could have done worse, it seemed.

Holo sulkily rolled over so that she was facing away from Lawrence. Given the obviousness of her actions, she was probably not so very furious.

“Why did you leave so early? The chicken and ale were both delicious.”

The villagers had brought out special ale, and it had been just as splendid as their claims suggested it would be. When Lawrence asked about it, they said that spices had been dried, ground, and added to the brew.

The chicken was so well fed that fat fairly dripped from it, so what could she be so unsatisfied with?

Holo did not immediately respond. Only after a fair span of time did she finally speak in a low moan. “Did you truly find that ale delicious?”

“Huh?” Lawrence responded, but not because Holo was speaking quietly.

“I could not drink it. I cannot believe anything so foul smelling would be called ‘delicious.’”

People had differing tastes, of course, so it was not hard to imagine that she would not find the heady scent of the ale to her liking. But why it would make her so angry, so sad—Lawrence could not guess at that.

His gaze wandered for a moment before he spoke very carefully, as though Holo were a bubble beside him that might pop at any moment.

“They put the spices of their homelands into it. It’s a very peculiar scent. For people who like that scent, it’s wonderful, but for those who don’t—”

“Fool.”

She kicked him under the blanket and then faced him.

Her features were distorted, but not by the moonlight that streamed in from the hole in the ceiling.

When she looked like this, Holo was holding back whatever it was that she truly wanted to say. And Lawrence never knew the reason why.

“Enough!” she finally said, then rolled back over and curled up tightly.

When they slept on the wagon bed, she would lay her tail on his legs—but not only did she snatch it away, she also took the blanket they had been sharing.

Her ears were turned away, making it all too clear she was in no mood to listen to him. It was evident enough from her turned back that she wanted him to take notice of something.

“…”

Surely she was not this displeased merely because the ale was not to her liking. She had broached this only as an excuse for her anger.

Lawrence reflected on how obsessed he’d been with gaining the village’s business ever since they had encountered the young man by the roadside.

He had heard that a hunter’s faithful hound would often become jealous when that hunter took a wife.

He wondered whether his reluctance to believe that Holo would feel similarly was the “foolish male” thinking that she’d accused him of.

Lawrence stole a glance at Holo’s back and then scratched his head.

In any case, he would have to pay more attention to her tomorrow.

This wolf’s mood changed just as often as the weather in the mountain forests from which she came.

In the winter drizzle, Lawrence would put his blanket over his

goods, shivering with his arms clasped around him as he passed the night. Compared with that experience, sleeping under a roof on a bed of straw was vastly preferable.

When morning came, he awoke with his usual sneeze, reflecting on such notions to avoid cursing the situation in which he’d found himself.

Next to him was Holo, curled up in her blanket asleep, snoring soundly.

He couldn’t claim not to have felt a twinge of anger.

But when he looked at her sleeping face, Lawrence could only sigh softly and stand from the bed.

While technically a house, it was still a roughly hewn dwelling dug into the earth.

His breath was white, and when he moved his body, his cold-stiffened joints creaked.

It was lucky that the floor was hard-packed earth rather than wood. He went outside without waking Holo and looked up at the sky—the weather would be fine, it seemed—and he yawned.

People were already gathering around the well to draw water, and in the distance the cries of oxen, pigs, and sheep could be heard.

It was the very picture of an industrious little village.

Lawrence couldn’t help but anticipate the coming morning. He smiled a rueful smile to himself.

It was near noontime when Holo finally awoke, and normally such sloth would be regarded with hard stares in villages like this.

But here everyone smiled, perhaps because they were all settlers. Nearly all of them had packed up their households and moved them, livestock and all, along a long and difficult road. They knew well that travelers had their own special sense of time.

Lawrence had been right that there wouldn’t be any breakfast, though.

It was considered a luxury even in the most prosperous towns, so of course it would be absent here in this simple, hardscrabble village.

“So, what are you doing?”

Lawrence wondered if Holo had slept in because she had known that there would be no breakfast.

In Holo’s hand were thin slices of boiled rye bread, between which were sausages made from pork slaughtered to preserve it over the winter.

It was a lunch that Lawrence would have felt guilty to receive for free, but unfortunately that had not been a problem.

As she chewed away on the food, Holo’s eyes followed Lawrence’s hands, which busied themselves with the task to which they’d been set.

Lawrence had a variety of things he wanted to tell Holo as she devoured her food and washed it down with ale, but given that her ire from the previous night had subsided, there seemed to be little reason to rouse it again.

Such thinking would probably result in spoiling her, but instead of saying any number of things, Lawrence answered her question.

“Translation.”

“Trans…lafuh?” she said.

It would have been absurd to warn her not to talk with her mouth full. Lawrence plucked a bread crumb from the corner of her mouth and nodded. “Yes. They asked me to translate this troublesome Church document into the language they’re familiar with, so that scuffles like yesterday’s won’t happen.”

It was work that would cost them a goodly amount if they had to go to a town to have it done.

Of course, while he was not charging them for the service, Lawrence was unable to guarantee the accuracy of his translation.

“Huh…” Her eyes half-lidded, Holo gazed at the parchment on the desk and the wooden slate Lawrence was using for his translation, but she finally seemed to lose interest and took a drink of ale. “Well, so long as you’re working I can keep eating and drinking without any hesitation.”

After tossing off this smile-freezing line, Holo popped the last remnant of lunch into her mouth and then moved away from Lawrence’s side.

“I wish you’d hesitate a little for my sake, at least,” Lawrence murmured to Holo’s back with a long-suffering sigh. He started to return to his work when he realized something. “Hey, that’s mine—”

No sooner had Lawrence said this than Holo was already chewing on her second piece of bread.

“Come, don’t make such a nasty face. ’Twas only a bit of a joke.”

“If it’s only a joke, why is there so little bread left?”

“I ought to be allowed to beg from you a little at least.”

“Such honor you do me,” said Lawrence sarcastically, which made a displeased Holo sit upon the table at which he was working.

He wondered whether she was about to flirt with him in her usual way when she suddenly looked down at him with a malicious smile. “Perhaps I’ll go beg from the villagers next time, then, eh? ‘Sir, sir, please, might I have some bread?’”

It hardly needed to be said whom such an act would harm. But if he gave in here, he really would be spoiling her.

“Just how many servings do you plan to eat, then?” he shot back, snatching the bread away from Holo’s clutches and returning to his work.

Holo drew her chin in irritably and sighed. It occurred to Lawrence that he was the one who should be sighing, but then—

“I suppose when the villagers ask me that question, I’ll put a hand to my belly and answer thus…”

Lawrence knew if he went along with this, he would lose. He picked up his quill as though refusing to listen.

“‘Well…I’m eating for two now, so…,’ I’ll say,” said Holo, leaning over and murmuring in Lawrence’s ear.

Lawrence spit the bread right out of his mouth, which was in no way a deliberate overreaction.

Holo smirked viciously. “What, is this the first time you’ve realized I eat enough for two?” she asked deliberately.

In negotiations, the winner was whoever used all the weapons at their disposal. Still, Holo used her weapons too well.

Just as Lawrence had decided not to listen further to a single word she said and was brushing the table free of crumbs, Holo’s hand shot out and plucked the link of sausage contained within the piece of bread.

“Heh. Come now, you’ve been working there since morning—you’ll get wrinkles on your forehead if you keep it up. Go outside and take in some of the cold air, eh?”

If Lawrence had been inclined to take her at her word, the way he had been when they’d first started their journey together, he would’ve told her to mind her own business—and thereby invited her ire.

Lawrence was silent for a moment, then closed his eyes and leaned back in his chair. He then raised a hand to about shoulder height to indicate his surrender and spoke. “I can’t let seed grain fall on a field that’s already been harvested.”

“Mm. I can’t promise I won’t take a liking to the wheat here.”

It was a joke only Holo-who-lived-in-wheat could tell.

She put her robe’s hood over her head, hid her swishing tail, and made for the door, putting out her hand to open it.

“It’s true that your taking a liking to the wheat here would be troublesome. I couldn’t stand to watch you eating food off the ground,” said Lawrence.

At this, Holo puffed out her cheeks in irritation and bit another piece off the bread that Lawrence held.

Taking a leisurely look around the village was not such a bad way to pass the time, and Holo hadn’t visited a normal village like this one since leaving Pasloe.

And while she might not have left Pasloe with much fondness, the atmosphere of the small farming village was still a comfortingly familiar one. She gazed at the hay, bundled and set aside as compost, and the tools leaning here and there, still dirty from use, all common sights back in Pasloe.

“They don’t have much trade with towns, so evidently they sow beans even during this season.”

Normally farming work was finished by this time of year, replaced by spinning and weaving or wood carving—indoor jobs all—but this village was apparently different.

The nearest town was three days away by horse cart, and worse, that town refused to do business with the village out of fear of accident.

Securing a food supply was the villagers’ first priority; every

thing else came after that.

“Beans are good for when the soil’s been exhausted. Of course, the earth here is good enough that they should be able to get good harvests for a while without worrying over such details.”

It didn’t take long for them to reach the edge of the village, and from there the fields continued for as far as they could see—an impressive feat given the village’s population.

Given that the fields lacked fences or trenches, the land was probably communally worked.

The forms of a few villagers could be seen in the direction of the spring, perhaps digging irrigation ditches.

The usefulness of a lie was suddenly clear, since just as Holo had said, the lines had disappeared from Lawrence’s forehead thanks to their excursion.

“So, how much do you suppose you’ll be able to wring from this village?”

The fence that enclosed the village was sturdier than its rickety appearance suggested. Holo sat on it, so Lawrence did likewise, waving to the villagers in the field who’d finally noticed them before he looked at Holo. “That’s not a very nice way to put it.”

“You were putting things much more nastily yesterday.”

For a moment Lawrence wondered if Holo’s ill temper the night before had been because he’d seemed too greedy. But no, given how amused she seemed now, that was surely not so.

“Profit is generated whenever goods are exchanged. If it’s going to come bubbling up without my having to do any work, I have only to drink my fill.”

“Hmm…As though ’twere wine, eh?”

She was talking about the wine made from drippings collected from skin or cloth bags of grapes hung from eaves. The grapes crushed themselves under their own weight, and the flavor was incomparable.

As usual, the wolf’s knowledge of food and drink was quite thorough.

“This time I ought to be able to turn a profit without relying on you. For an opportunity met through happenstance by the wayside, it’s quite large. Even if you do stuff yourself with chicken.”

A gentle breeze blew, and the mooing calls of cattle could be heard in the distance. He barely had enough time to notice how quiet it was before the piercing clucking of chickens sounded behind them.

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 2

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 2 Wolf & Parchment, Volume 3

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 3 Spring Log II

Spring Log II Spring Log IV

Spring Log IV Wolf & Parchment: New Theory Spice & Wolf, Vol. 4

Wolf & Parchment: New Theory Spice & Wolf, Vol. 4 Spring Log III

Spring Log III Spice & Wolf IV

Spice & Wolf IV Spice & Wolf X (DWT)

Spice & Wolf X (DWT) Spice and Wolf Vol. 2

Spice and Wolf Vol. 2 Spice & Wolf XIII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XIII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 10

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 10 Spice & Wolf XVI (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XVI (DWT) Town of Strife I

Town of Strife I Spice and Wolf, Vol. 5

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 5 Side Colors II

Side Colors II Wolf & Parchment, Volume 1

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 1 Spice & Wolf Omnibus

Spice & Wolf Omnibus Spice & Wolf XII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XII (DWT) spice & wolf v3

spice & wolf v3 Spice & Wolf

Spice & Wolf Spice & Wolf VIII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf VIII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 4

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 4 Spice & Wolf XIV (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XIV (DWT) Spring Log

Spring Log Spice & Wolf III

Spice & Wolf III Spice & Wolf VII - Side Colors

Spice & Wolf VII - Side Colors Spice & Wolf XV (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XV (DWT) Side Colors

Side Colors Side Colors III

Side Colors III Spice & Wolf VI

Spice & Wolf VI Spice & Wolf IX (DWT)

Spice & Wolf IX (DWT) Spice & Wolf V

Spice & Wolf V Town of Strife II

Town of Strife II Spice & Wolf XI (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XI (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 12

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 12 Spice and Wolf, Vol. 3

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 3 Spice and Wolf, Vol. 1

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 1 Spice & Wolf XVII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XVII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 6

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 6 Spice & Wolf II

Spice & Wolf II