- Home

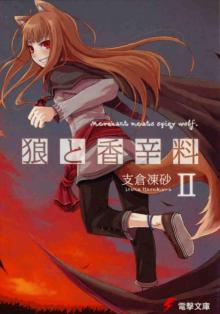

- Isuna Hasekura

Spring Log II Page 3

Spring Log II Read online

Page 3

“Hmm. Now we can relax a bit.”

When they arrived at the house, Holo finally emerged from the wagon bed, and Amalie was happy to see her dressed as a nun but disappointed when she learned the outfit was only a means to an end for their journey.

It seemed this landlady was still thinking about the abbey.

On the other hand, due to the morals she had cultivated at the abbey, Amalie was a bit apprehensive about placing Lawrence and Holo in the same room. So he told her that once he was finished working as a traveling merchant, they were planning on opening a store and getting married.

It was not a lie, but it felt like one since it did not seem real for some reason, and perhaps he was expecting Holo’s mood to improve once he said this.

After they had been led into the room (but before Lawrence could set down any luggage), Holo collapsed onto the bed.

Then she finally talked to him.

“You fool.”

Lawrence packed their things into the long chest in the room and turned back to her.

“You will go anywhere to aid helpless females, will you not?”

The nuance in her words was less “softhearted” and more “cheater.”

“No, actually…”

Lawrence was about to make an excuse when Holo buried her face into the pillow and heaved a long sigh before glancing sideways at him.

“Silence.”

He had no choice but to do what he was told.

Lawrence obediently closed his mouth, and Holo took a deep breath and rustled her tail under her robe. Her expression was more exasperated than angry.

“Sigh…I was displeased by what an inattentive idiot you are, but to think that you were actually a fool who did not notice the ruler of this land was female in the first place!”

It seemed she had completely noticed his surprise when he saw that the girl who appeared from the village head’s house was the landlord.

“You are an extraordinary idiot.”

“I assumed the landlord would be a man.”

Lawrence gave his response, and Holo turned the opposite way in a huff.

However, that was not rejection but something else entirely.

Unwilling to give up, he sighed, then sat down on a corner of the bed that Holo was lying on.

“I had no idea that was why you were in such a bad mood.”

“…”

Holo did not look at him, but the wolf ears on her exposed head were facing him. The triangular ears of the wisewolf could hear the ring of any lie being told.

After moving her ears this way and that for a bit, she slowly turned to face him again.

“Hmph. Why would I be in a bad mood? You are not bold enough to cheat on me, not to mention, you are not handsome enough to attract other females.”

They were meant to be harsh words, but Lawrence desperately held back a laugh.

Holo had been jealous over Lawrence’s apparent eagerness to head toward Hadish in aid of an ignorant girl who had been suddenly called home from a girls’ abbey. Though there was likely nothing between them, he must have seemed oddly worried about this female ruler.

On the other hand, the very same Lawrence had not even considered the possibility that the landlord would be a lady.

Her verbal barb had been the result of experiencing such unnecessary anxiety.

Of course, it was cute.

Lawrence reached out to Holo’s head and ran his fingers through her soft, flaxen-colored hair.

“That may be true.”

The only one who would spend this much time with him was the bighearted wisewolf.

Even if he saw through her facade, no matter how much of an act she put on, that appearance was what counted.

“But you might like watching me gallantly saving troubled girls, huh?”

Her ears twitched as he stroked her head, and she smiled with her eyes closed.

“…Fool.”

Though she was not entirely happy with this detour, she did not stubbornly oppose it, likely for this reason.

Lawrence believed that he and Holo were very similar when it came to their good nature and that she would be proud of him if he helped somebody.

More confidently, he also thought that Holo would find him more attractive.

If he said that out loud, she would laugh at him and drag him through the dirt, but then in the end, she would look at him with eyes filled with expectation. And if he did well, she would praise him.

Her rustling tail had finally fallen silent.

It was quiet for a few moments.

Lawrence leaned over to kiss Holo on the cheek, but her hands suddenly flew up and landed on both sides of his face, holding him there.

“Bathe first.”

She then thrust him aside.

“…Is it really that bad?”

Lawrence sniffed his clothes, but he really could not tell.

But if the princess said so, then he had to obey.

“And you have work to do. It all seemed rather troublesome. Will you be all right? I shall not allow you to endanger yourself around me, aye?”

Despite sulking in the wagon bed, she had clearly heard everything.

But if he mentioned it, she would definitely get mad and refuse to let him hug her tail during the night.

“Your powers could solve this instantly.”

Holo snorted at his declaration, hugging the pillow.

“I am not a dog.”

Lawrence shrugged and stood up.

“Finding a hand mill itself isn’t hard.”

The argument with the villagers that Amalie had explained on the way was essentially about money, starting with the repairs of the water mill.

The structure had been neglected for a long time, and after they called on a repairman, it turned out the work would require quite a lot of money. Though it never really functioned well, it fell apart completely after being neglected in the confusion of the sudden succession. In reality, the mill belonged to the ones who owned the land, but the Draustem family did not have enough funds to repair it on their own. And since it was operated by the fees the villagers paid when they used it, Amalie took Yergin’s advice and came to a very logical solution: collect installation costs from the villagers.

Of course, many villagers objected. Not all of them relied on the water mill to the same extent. The ones who would gain from the installation of the water mill would be the families who owned extensive fields and those with lots of sheep.

Or perhaps, it would be easier for households without young workers to use the water mill by paying money. Even the Draustem family themselves needed the water mill, as they collected wheat as taxes and land usage fees.

On the other hand, what was left over from the fees to use the water mill would not be added to the Draustem family coffers, but instead go toward mending bridges and fixing roads. So until recently, it was a rule that the villagers used the water mill when grinding their wheat into flour.

However, from the perspective of the villagers, whose precious coin would be collected, they wanted to avoid using the mill if they could.

And so, since the time of the previous landlord, the villagers secretly produced hand mills so that they would not have to use the water mill.

Amalie went into direct negotiations to resolve the situation.

“If those hand mills or whatnot are the reason why they refrain from using the water mill, then ’tis logical to retrieve them, but…Hmm, how shall I say this?”

“Precisely. You’re earnest.”

“Unlike you.”

He looked at Holo, and he found a smile beaming on her tilted head.

“You are soft—’tis a compliment.”

Her teasing was proof that she was in a better mood, so he simply left it at that with a shrug.

“So do you plan to help this little girl?”

“I do. The reason why is Miss Amalie. But…”

“But?”

“You heard, too, didn�

��t you? The water mill catches fire almost every year.”

It was the biggest factor in why Amalie’s explanation was somewhat hard to understand and a key reason the villagers were so opposed to her plan.

“I cannot believe it so readily.”

The water mill was built on a river, and water flowed through the river. And as long as there were no candles around it at night, there was almost no danger of accidental fires.

But when Lawrence had spotted the building from far away, it certainly seemed a bit dark. That had not been mold but the traces of fire.

It seemed that was the reason why the village houses were built so far from one another as well.

“To think that flower field catches fire every summer and becomes a sea of flames…’Tis unthinkable in the land we lived in.”

It was something that happened occasionally to oily flowering plants, and it had the worrying characteristic of blooming in spring and bearing fruit in the summer, when the sunlight would cause it to burst into flames, spreading its seeds to sprout again in the burned fields. Of course, other plants and flowers naturally burned to ash in the fire, so once those flowers began taking root in an area, they soon dominated as the only things left standing.

Misfortune befell the village when these flowers took root one day by chance and flourished.

According to Amalie, they were not around during her grandfather’s time, and out of the entire region, it was only in the vicinity of Hadish where this plant grew.

“So the fire finally dies down around the river, but the nearby flames scorch the water mill, and it keeps falling apart. In the past, the houses would burn whenever there was a brush fire, and since they needed lots of lumber, all the surrounding forests became fields.”

“’Tis quite wise they spaced their houses out to prevent them from all being killed at once.”

The area had few inhabitants because they sacrificed the forests to harvest materials to build their homes, and half the space had been taken over by those purple flowers.

“To make sure the reconstructed water mill stays around a long time, they would need to cut down as many of those flowers as possible before summer comes, but it’s the busy season and the villagers don’t want to help.”

“No water mill means they would not have to go through the trouble, perhaps.”

But if they are unable to grind the wheat into flour, then they could not make bread, and it took too much time to grind by hand. It signaled that, in the bigger picture, the villagers’ productivity would drop—and consequently their tax revenue—and the village’s economy would wither. With the water mill, they could save that time, giving them a chance to cultivate more fields. They could sell the surplus goods in towns and gain the ability to buy many things. From a top-down perspective, it was clearly for the villagers’ sake.

It was apparently Yergin who explained this to Amalie, and Yergin himself learned that from the previous landlord, who seemed to have been a wise ruler.

That being said, others did not always accept sound arguments, which led to the current situation.

“Mr. Yergin said he could confiscate the hand mills by force, but they want to avoid that if possible. It would only cause problems later. So Miss Amalie went to them herself and was hoping the villagers would hand over the mills on their own.”

“Hmm. But would it not be the same if you found and confiscated the mills in secret?”

Holo said this without particularly thinking.

Lawrence smiled ironically and answered.

“No. Mr. Yergin and Miss Amalie live here. But I’m a traveling merchant. It’s the travelers who bring misfortune to villages. If we make it so that I was the one who put an idea into Miss Amalie’s head, then I’ll be the target of the villagers’ resentment. And so when I leave, then the person who everyone hates simply disappears. I don’t think Miss Amalie has thought of this, but it seems like Mr. Yergin is already well aware of how to best use me. That’s probably why they’ve given us such a nice room.”

Traveling merchants, who never settled in one place, derived their value from the very characteristic Lawrence had just described. They brought things the villages needed, then took away what they did not need. Even Holo, who was once called a god who governed the harvests of wheat, had experienced this treatment.

A god could never be a member of a village, and though they were worshipped during farming seasons, they were blamed for bad harvests, and the fault of every other sort of misfortune the god had no control over was still laid at their feet. People could not vent their anger on their fellow villagers, but if they blamed outsiders, all was well that ends well. In the end, once they no longer needed their god, they stopped worshipping it completely.

And so Holo had snuck into Lawrence’s wagon.

When he thought about it, he noticed that the way they met was much like how similar tools were stored away in the same place since there was no other place to put them.

But Lawrence did not consider his job an unhappy one.

Because it was thanks to his work that he had met Holo.

“Don’t make that face.”

Lawrence’s smile was a bit forced. Seeing Holo’s hurt expression, he moved to pinch her small nose.

“Now that I have someone to share my burden with me on the driver’s perch, what else do I need?”

“…Fool.”

She knocked his hand away and spoke grumpily. Only her tail was restless.

“Would you truly be able to find the mills, however? Should the time call for it, I may be able to find them by the scent of the wheat.”

Holo spoke up, but this time, Lawrence showed her a boastful smile.

“If this is a contest of cunning, I won’t lose, you know!”

He puffed out his chest, and after Holo gave him a blank stare, she chuckled.

“Perhaps you have mistaken it for shallow wit.”

“You judge harshly.”

Lawrence shrugged, and Holo intertwined her index finger with his, which she had just been gripping. She was more of a lady than he thought.

So Lawrence, who acknowledged himself as a gentleman, laid out his words tentatively.

“Well, it probably won’t be very fun, so you don’t have to come collect the mills if you don’t want.”

Holo, still smiling, brought Lawrence’s hand up to her mouth and bared her fangs.

“I am quite fond of seeing your face blubbering with tears.”

“Oh, I see we’ll get along, then.”

Holo’s ears and tail twitched happily.

“Fool.”

Holo smiled, leaned her head against him, and kissed his hand.

Then she let go.

“Then I shall be watching how you work.”

Before long, there was a knock on the door and Yergin came to call on them.

The bread they were given was far from fresh, but it was good white bread made from wheat. Moreover, the soup was not simply seasoned with salt and vinegar but had been thickened with bread crumbs, and it contained large chunks of lamb.

But most surprising was the liquor bottle on the table.

“What a gorgeous bottle. It’s a lovely shade of green.”

Once Amalie finished the long, long prayer she had learned from the abbey, the meal finally began in earnest, and Lawrence broached the subject with his curious comment.

“It was my father’s hobby, it seems. There are many things fashioned from glass in the basement of the manor…There are truly so many I thought maybe I could keep some and sell the rest and use that to cover the costs of the water mill, but…”

Amalie spoke apprehensively, and Yergin, sitting uncomfortably at a corner of the table, glanced at Lawrence. His awkwardness stemmed from his large stature but was also likely due to an outlook of his that probably said master and servant did not sit at the same table.

Between the two of them, it seemed there was a great difference in their ways of thinking, and that appare

ntly applied to the glass collection as well.

Amalie, with an impartial spirit, most certainly thought of selling the glass, but for Yergin, there was no doubt that even thinking of such a thing was outrageous. Heirlooms that belonged to the previous landlord were the same as family treasures.

“If you forbade the use of the hand mills, however, you might solve the water mill problem for the time being.” Lawrence offered his suggestion as he broke off a piece of bread and dipped it into his soup. “I’ve seen a similar thing happen somewhere else in the past. I am sure I can help you.”

Then, Yergin sat up straight again. It was as though he realized that Lawrence also understood.

“You can?”

“Yes. Even in wide-open farming villages, there really aren’t that many places to hide things.”

When she heard the word hide, her twinkling expression quickly deflated.

She was most certainly hoping that the villagers would help her of their own free will.

Lawrence took a sip of wine, then spoke like a cruel, money-mad man.

“There’s no need to worry. It is even worse to avoid paying taxes.”

He smiled as though that were simply the course of things.

Amalie grimaced, but she did not look to Yergin because she knew that he was not on her side.

“The installation of the water mill is for the sake of the village, after all. Oh, and of course, I will not do anything that would trouble you, Lady Amalie. I can collect the hand mills.”

“Oh, but you—”

“Of course, it would be difficult to carry the hand mills, so I wish to ask Mr. Yergin’s assistance.”

Amalie was a smart girl. She immediately realized that she needed to distance herself from the dirty work that would take place. But she also had a kind heart that felt confusion and guilt about doing such a thing.

And then there was Yergin, who responded in a hard tone of voice.

“Any time.”

Amalie looked between Lawrence and Yergin with a dejected expression and stared toward her feet. The seat of authority was not as comfortable as some assumed, and it was not meant for everyone.

But Lawrence considered Amalie once more. For better or worse, people could grow used to power.

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 2

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 2 Wolf & Parchment, Volume 3

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 3 Spring Log II

Spring Log II Spring Log IV

Spring Log IV Wolf & Parchment: New Theory Spice & Wolf, Vol. 4

Wolf & Parchment: New Theory Spice & Wolf, Vol. 4 Spring Log III

Spring Log III Spice & Wolf IV

Spice & Wolf IV Spice & Wolf X (DWT)

Spice & Wolf X (DWT) Spice and Wolf Vol. 2

Spice and Wolf Vol. 2 Spice & Wolf XIII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XIII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 10

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 10 Spice & Wolf XVI (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XVI (DWT) Town of Strife I

Town of Strife I Spice and Wolf, Vol. 5

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 5 Side Colors II

Side Colors II Wolf & Parchment, Volume 1

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 1 Spice & Wolf Omnibus

Spice & Wolf Omnibus Spice & Wolf XII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XII (DWT) spice & wolf v3

spice & wolf v3 Spice & Wolf

Spice & Wolf Spice & Wolf VIII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf VIII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 4

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 4 Spice & Wolf XIV (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XIV (DWT) Spring Log

Spring Log Spice & Wolf III

Spice & Wolf III Spice & Wolf VII - Side Colors

Spice & Wolf VII - Side Colors Spice & Wolf XV (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XV (DWT) Side Colors

Side Colors Side Colors III

Side Colors III Spice & Wolf VI

Spice & Wolf VI Spice & Wolf IX (DWT)

Spice & Wolf IX (DWT) Spice & Wolf V

Spice & Wolf V Town of Strife II

Town of Strife II Spice & Wolf XI (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XI (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 12

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 12 Spice and Wolf, Vol. 3

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 3 Spice and Wolf, Vol. 1

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 1 Spice & Wolf XVII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XVII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 6

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 6 Spice & Wolf II

Spice & Wolf II