- Home

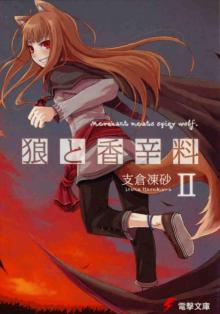

- Isuna Hasekura

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 12 Page 2

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 12 Read online

Page 2

Just as Huskins had so aptly said, whenever the old gods were driven from their forests and mountains, merchants were always behind it. They were not even bothering to hide themselves this time.

“This is probably because so many were put in a bind with the cancellation of the northern campaign. No one wants war where they live, but if it’s a far-off land, it’s a welcome event. Foodstuffs and supplies fly off the shelves, and the mercenaries that plague fields and villages are all occupied far away. If things go well, nobles that went off to war return rich with plunder, which may then be shared.”

“And so much the better if the land attacked is a pagan one, eh?” said Holo.

Holo’s homeland of Yoitsu had been destroyed centuries earlier, so the story went. But the forests and rivers she knew should still be there, along with a sunny hilltop somewhere where she could nap. In that sense, her homelands should still exist.

But the search for gold, silver, or other metals would literally change the landscape. Trees would be felled, rivers dammed. In but a moment, it would become a place she had never seen before.

“Er—” Col politely raised his hand, seemingly on the verge of tears. He was another of the few who were taking action to protect their homes from the Church’s oppression. “Do we know where, um, the attack will happen?”

“We do not. However,” said Lawrence, giving the boy a comforting smile, “we can prepare. The larger the operation, the more impossible it becomes to hide. Even if we can’t stop things entirely, we can turn the spearpoint away from the places we want to protect.”

Col nodded, a pained look on his face. He bit his lower lip.

Twenty years hence, it was possible that Col would have sufficient influence within the Church to turn that spearpoint himself. But that was still merely hypothetical.

Holo reached out to stroke Col’s cheek and then gave it a pinch. When she spoke, it was to Lawrence. “What will we need?”

“First, an accurate map of the northlands. Having learned a place-name, it’ll do us no good if we don’t know where that place actually is, and we won’t know where war is spreading, either. And while it’s not exactly a minor detail, we may find more news of the wolf bone in the process.”

Holo nodded and took a deep breath.

“That’s why I had Mr. Huskins give me the name of someone who could give us news of the north and draw us a proper map. And since he knows the truth about the wolf among us, I expect the introduction will be a good one,” said Lawrence jokingly.

Holo only sniffed, unamused, while the guileless Col nodded. This was what Lawrence had told Holo when they’d greeted the morning at the abbey.

He could gather information and take her back to her homelands, as he had first promised, but any heroics that might follow—such as ruining the Debau Company’s plans—were beyond his ability to guarantee.

Their opponent was a great trading company that controlled the mines of the north. It was a world that would take more than mere money to navigate. Getting Brondel Abbey to sell a holy relic to the Jean Company was only one small part of the Debau Company’s goal.

When he had learned this from Huskins, before feelings of resentment set in, Lawrence had been simply amazed at the ridiculous breadth of the world.

His own influence had its limits, and traveling merchants were generally a powerless lot. But Holo did not blame him for that, so Lawrence felt no shame.

He would do what he could. And what he could do, he would do to the absolute best of his ability.

“In any case, we’ll return to Kerube. There we’ll meet with a certain merchant.”

Kerube had been consumed with the narwhal disturbance. Holo put the question to him with a look of distaste. “Not to that runt that caused you so much fuss surely?”

“You mean Kieman? No. A merchant who’s one of Huskins’s friends.”

At Lawrence’s answer, Holo’s expression turned still sourer. “We’re relying on the power of sheep yet again…?”

“It’s not a shepherd this time. That’s got to be some sort of improvement.”

Holo was not a high-handed noblewoman. It was true she did possess a certain measure of pride, but it was a childlike vanity and stubbornness that she often employed, which she herself would readily admit.

Lawrence did not expect a reply to his statement, but he got one.

“If not a shepherd, what then?”

Lawrence’s answer was simple. “An art seller.”

Just as rivers divide one nation from another, the climates on opposite sides of even a narrow sea channel can be very different. Different enough that letters exchanged across it often give rise to jokes that summer and winter come at opposite times.

While the port town of Kerube was still cold, it was not icily so. But if one crossed the river that flowed through the town and headed north, the scenery would soon turn a pure white that was not so very different from Winfiel. The world was a strange place.

“So will we disembark on the north side? Or the south?” asked Holo with tired eyes from underneath the blanket as they rode within the ship. She had started drinking wine not long before, insisting that it was too cold not to.

Lawrence put his hand on Holo’s head and idly brushed her bangs aside before answering. “The south. The livelier side.”

The town of Kerube was divided down the middle by a river. On the north side lived the original inhabitants of the town, while the south was full of more recently arrived merchants. The livelier half was the south, where the merchants were.

“Mmm. I suppose…I’ll be able to look forward to a tasty dinner, then,” Holo said, yawning as she spoke, then smacking her lips. Lawrence wondered what sort of feast she saw at the end of her gaze.

Thinking of the contents of his coin purse, he replied with a bit of a jab, “Joking aside, how many sheep might we have had?”

Huskins was employed as a shepherd at Brondel Abbey, and he had offered over and over to quietly give them several head of fine sheep.

“Mm…’twould have been no small trouble to bring them with us.”

“I never would have thought you’d play the realist.”

Sheep were costly, and those chosen by the golden sheep Huskins himself would surely leave nothing to be desired. But they had not accepted his offer for exactly the reason Holo had just stated.

When Lawrence turned Huskins down, Holo had clearly been displeased, but even then she had understood.

“I can manage that much, at least,” said Holo. “After all, our pack is already…” Using their belongings for a pillow, Holo lay under a blanket. Lawrence’s hand was on her head, and from underneath it she looked up at him mischievously. She did not finish her sentence, though, either out of kindness or having decided it was more trouble than it was worth.

“How about you sleep quietly, like Col?”

Col was afraid of traveling by ship, and after a swallow of wine had slept soundly by Lawrence’s other side.

At Lawrence’s words, Holo slowly closed her eyes and answered, “I don’t fear ships, but wine. If I could but sleep I could escape the fear, but to do that I fear I need to drink more.”

An old joke, one often directed at the clergy, who were prohibited from drinking. What made Holo so frightening was not that she knew the joke, but that she was able to seem like she truly meant it.

“I fear the cost of food, so I’ve nothing to drink but my tears,” said Lawrence.

There was no reply from the perhaps unamused Holo.

Some time later, the ship arrived as planned in Kerube.

By the time Lawrence woke Col, and grumbling, Holo got to her feet, Lawrence and company were the only ones left in the ship’s hold.

“Ngh…whew. ’Tis been but a few days, but this feels strangely nostalgic,” said Holo once they left the ship and found themselves standing in the south side of the town. Having been swept up in the chaos that threatened to divide the town in two, perhaps it had left a deeper-than

-usual impression on them.

“Could be because the snowy scenery of Winfiel is so different from things here. But you’re right.” Lawrence divided their luggage between himself and Col and then held the hem of Holo’s cloak down to keep her tail from showing as she stretched. “This is the first time we’ve returned to a town we’ve already visited.”

“Mm? Oh, aye. Now that you mention it, ’tis so.”

After the sad state of Winfiel, it was even easier to appreciate the constant hustle and bustle of Kerube. For all those who made their lives by trade, a lively marketplace was best.

“Indeed, it does feel as though we’ve been traveling together for a terribly long time.”

“Hmm?”

Holo narrowed her eyes and looked around, then clasped her hands behind her and started to walk forward. “And every time we enter a new town, something worth laughing about for fifty years seems to happen.”

Something about her form seemed terribly lonely, and Lawrence was sure it was not just his imagination. If Holo was to laugh at these memories fifty years from now, he would not be by her side to join her.

“…”

When Lawrence failed to muster any response, Holo turned around to face him. “So then, shall we add another happy memory to our travels?”

Lawrence looked past Holo, where beneath the eaves of a shop, eels were being fried in oil.

Having left their things at a trading house, Lawrence went to Kieman, who had written him an introduction letter, to tell him in an innocuous way about recent events there.

Kieman, amused, listened all the while and, in lieu of a reply, held out a letter sent to the trading company some days earlier from a town farther south that was famous for its furs.

The letter contained but a single sentence: “We profited.” Lawrence was sure that if he put his nose to the paper, he would catch the scent of a wolf—but that wolf was not Holo.

He did not need to ask who the letter was from.

“An art seller? Oh, perhaps you mean the Hugues Company.”

“Yes, I’d like to meet with Hafner Hugues.”

“If you simply head out the front entrance of the trading house and down the street, it will be on your right. They’ve a signboard with a picture of a ram’s horn hanging from the eaves, so they’re hard to miss.”

Lawrence smiled wryly at that detail—it was a bold sign to have, given that Hugues was one of Huskins’s kind.

“Still, it’s unusual that you would have business with the Hugues Company.”

Art was the purview of the wealthy and powerful, so it was rare for a traveling merchant like Lawrence to walk into an art seller’s company. As someone concerned with the reputation of the Rowen Trade Guild, Kieman was undoubtedly worried that Lawrence was again involved in something strange.

Lawrence probably could not sweep those worries away, but Kieman might know something useful, so Lawrence replied even as he held no particular expectations. “I hope to meet with a silversmith named Fran Vonely.”

Huskins had given him the name, and when Kieman heard it, his face was the very image of surprise.

“Do you know her?” Lawrence asked.

Kieman rubbed his face to erase the shock, then smiled faintly. “She’s famous. Or perhaps I should say notorious.”

What was that supposed to mean? Lawrence quickly looked around, wordlessly pressing Kieman to continue.

“It’s her clientele.”

Kieman’s eyes in that moment seemed to evidence more worry for Lawrence than they did concern about speaking ill of Fran Vonely.

“She’s celebrated for having such high patrons for such a young silversmith, but those patrons are all newly wealthy, and most of them have dark shadows in their pasts. And she won’t hear questions about where she apprenticed or who her master was. She’s very mysterious.”

Kieman’s information sources were like a spiderweb over the land, so his words were undoubtedly true.

What sort of person was she?

As Lawrence mused, Kieman said one last thing. “I think you’d be better off avoiding her.”

Within their organization, the difference between Kieman and Lawrence was like that between heaven and earth. If Kieman made a suggestion, it was meant as an order. And yet as Kieman’s pen danced over his ledger book, he murmured one last thing.

“Ah, seems I’ve been thinking aloud again.” A deliberate smile flickered across his features; it seemed he really did intend the warning as well-meaning advice.

Lawrence bowed to Kieman and then hurried to leave the trading house, where Holo and Col awaited him.

As he went, Kieman offered one final statement without looking up from his ledger. “Let me know when you’ve profit to divide.”

It seemed presumptive to think of Kieman as a friend, but they did share a friendly sort of tie, Lawrence felt. “But of course,” he said with a smile before putting the trading house behind him.

“Did things go well?” asked a worried Col. And no wonder—normally it would be distasteful to even meet the eye of someone whose greed had caused the trouble for them that Kieman’s had.

But in all the world, none were so ready to put grudges behind them and drink with onetime enemies as merchants were.

Lawrence patted Col on the head. “Seems they got a letter. ‘We profited,’ it said.”

Col’s face lit up; he had always liked and worried about Eve. And Eve, too, seemed to be fond of Col.

The only displeased one was Holo.

“I only pray this doesn’t mean that more misfortune awaits us.”

She was no doubt referring both to Eve—who had once actually tried to kill Lawrence—as well as Fran Vonely and the warning from Kieman.

As far as they had heard, she would be a troublesome person to deal with.

Lawrence gave Holo a look that said, “You’re hardly one to talk.”

Holo sniffed in irritation. “So where are these art sellers to be found?” The obviousness of her ill temper made clear she was not really unhappy at all. When Lawrence started walking, she immediately followed.

Once she saw the signboard that hung from the eaves of the Hugues Company, she fought back a wry smile. “I’m not sure whether they’re gutless or bold.”

“Probably for the same reason you see so many eagles on the nobility’s family crests,” said Lawrence, opening the shop’s door, which was simply made but finely carved and had likely cost a good sum. Immediately his nose was hit by the smell of paint.

The shop was on the small side for one on such a busy street, but Lawrence was immediately struck by how profitable it probably was. There was no small number of paintings hanging on every wall, and they all had one thing in common.

They were large.

In general, it was neither the subject nor the artist of a painting that determined its price. Most of a painting’s price was in the paint itself, and so it was the size and color quality of a piece that decided its value.

Every painting in this little shop was large and had been rendered in many vivid colors. They were undoubtedly worth a significant amount.

“Ho…”

Some of the paintings depicted God or the Holy Mother, while others showed saints in reclusion, in mountains and forests, in caves and by ponds. In each case, the backgrounds seemed more prominent than the subjects, as though the artists had cared more about them than God or the Holy Mother.

“Perhaps no one’s home.”

Holo seemed impressed, and her breath quickened. Col was silent. Lawrence ignored them and went farther into the shop—but not before turning around and giving Holo a stern warning. “Don’t touch the paintings.”

Holo’s cheeks immediately puffed out in irritation at being scolded like a child, but she did indeed have a finger raised and pointed at the face of one of the paintings. If she touched it and left a mark, they would all have to beat a hasty retreat.

“Excuse me! Is anyone here?” Lawrence called out into the s

hop, which elicited the slam of a closing door. There seemed to be someone in the storeroom.

Lawrence heard a muffled reply and gazed at one of the paintings on the wall as he waited for the shopkeeper to emerge. It was a painting of a group of pilgrims on their journey. They were walking alongside a river, on the opposite side of which was a lush forest and grand mountain range.

The man who finally emerged from the back of the shop looked more like a pig than a sheep. “Yes, yes, how may I help you?”

A glance at the flat cap on his head called to mind a clergyman, but he was dressed in fine merchant’s clothes.

“I’m here to see Mr. Hafner Hugues.”

“Oh? Well, I’m Hafner. So…how might I be of assistance?”

Lawrence was obviously a traveling merchant, and his companions were equally obvious as a nun and a rescued street urchin. None of them were the usual clientele for an art seller who catered to the wealthy.

“Actually, I was sent by Mr. Huskins from Brondel Abbey…”

That was as far as Lawrence got.

Hugues’s piglike nose twitched, and his eyes were fixed in a corner of the room.

Holo noticed his gaze and looked up from a picture of the Holy Mother holding an apple.

Holo was small, but she was still a wolf.

“Ah…ah…ah…”

“Her name is Holo,” said Lawrence, smiling brilliantly at the terrified Hugues.

But Hugues did not have the wherewithal to listen. He seemed ready to flee but unable to make his legs move, and he gazed at Holo as though poleaxed.

It was Holo who moved.

Without so much as a sigh, she walked right up to him. “I don’t suppose you have any apples like the one in that painting?”

When surrounded by a pack of wild dogs in the forest, about the only thing one can do is pull out a piece of jerky and throw it as far as possible.

The effect was immediate. Hugues nodded so quickly his fleshy cheeks jiggled before he immediately disappeared into the rear of the shop.

“He’s more pig than sheep, I’d say,” mused Holo as she watched him go.

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 2

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 2 Wolf & Parchment, Volume 3

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 3 Spring Log II

Spring Log II Spring Log IV

Spring Log IV Wolf & Parchment: New Theory Spice & Wolf, Vol. 4

Wolf & Parchment: New Theory Spice & Wolf, Vol. 4 Spring Log III

Spring Log III Spice & Wolf IV

Spice & Wolf IV Spice & Wolf X (DWT)

Spice & Wolf X (DWT) Spice and Wolf Vol. 2

Spice and Wolf Vol. 2 Spice & Wolf XIII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XIII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 10

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 10 Spice & Wolf XVI (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XVI (DWT) Town of Strife I

Town of Strife I Spice and Wolf, Vol. 5

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 5 Side Colors II

Side Colors II Wolf & Parchment, Volume 1

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 1 Spice & Wolf Omnibus

Spice & Wolf Omnibus Spice & Wolf XII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XII (DWT) spice & wolf v3

spice & wolf v3 Spice & Wolf

Spice & Wolf Spice & Wolf VIII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf VIII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 4

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 4 Spice & Wolf XIV (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XIV (DWT) Spring Log

Spring Log Spice & Wolf III

Spice & Wolf III Spice & Wolf VII - Side Colors

Spice & Wolf VII - Side Colors Spice & Wolf XV (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XV (DWT) Side Colors

Side Colors Side Colors III

Side Colors III Spice & Wolf VI

Spice & Wolf VI Spice & Wolf IX (DWT)

Spice & Wolf IX (DWT) Spice & Wolf V

Spice & Wolf V Town of Strife II

Town of Strife II Spice & Wolf XI (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XI (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 12

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 12 Spice and Wolf, Vol. 3

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 3 Spice and Wolf, Vol. 1

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 1 Spice & Wolf XVII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XVII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 6

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 6 Spice & Wolf II

Spice & Wolf II