- Home

- Isuna Hasekura

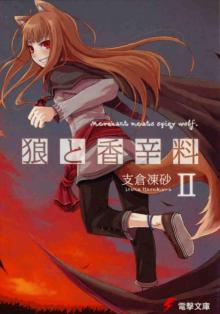

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 2 Page 16

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 2 Read online

Page 16

In his own way, Reicher was pouring his all into this land he had washed up on.

If that was the case, then the merchants in the courtyard who had waved to him so congenially must not have had the friendliest of relationships with him. It was more likely they thought of Reicher as a traitor, while considering the people of the island to be friends of the merchants. This man had lost all his spirit, except that which could be found in alcohol.

“What’s more, the Ruvik Alliance, an important pillar in the support of this church, is discussing the possibility of reducing the number of the islanders’ boats even more. Our savings will diminish, too.”

Praying would not fill an empty stomach, nor would it free anyone from the shackles of monetary transactions.

What this land needed was money.

And what did not add up in the balance books, Autumn took upon himself as his personal sin.

Reicher was drinking likely because he felt like his guilt would crush him even now.

Had Col and Myuri not been there, it would have ended up the same. Col looked at the girl beside him, and her beautiful red eyes stared back at him questioningly.

While they were in their exchange, Reicher adjusted himself in the chair, removed the cork from the cask, and took a swig.

“…Pahh. This is unacceptable as a clergyman, but…”

The man certainly drank like a bandit.

That was what Col was imagining, but Reicher’s next words were painful.

“I wish war would break out soon.”

“…War?”

Autumn stood at the head of seafaring pirates. Those aboard ships gathered information, allowing him to know right away that Col and Myuri, who had so shamelessly wandered in, were working for Winfiel.

Col thought that Reicher might be the same, but the priest took another swig from his cask and exhaled painfully.

“…Guh. W-war. Winfiel has risen in revolt against the pope’s tyranny, and the fire has finally been kindled in Atiph. Now, it’s just talk about when it might all go up in flames. When it does, I just know that the islanders’ manpower and fishing industry will play a crucial role.”

Reicher was about to drink more, but Col, of course, stopped him. He was drinking like he was trying to end himself.

“Mr. Reicher.”

“…Who will weep for me if I die? I know even God has already forgotten my name.”

He smiled in bitter irony, but he did not try to force himself to imbibe again. Perhaps he had wanted someone to stop him.

He placed the cask on his lap limply, then looked up to the heavens and closed his eyes.

“If war broke out…then the price of fish would rise. Many of the islanders might become distinguished soldiers. The kingdom, the pope, whoever we work with, the reward will be the same.”

Reicher talked as though to himself. He knew that even if they earned some money that way, they would only be comfortable for but a moment. And while it was almost certain some would thrive in the war, there were many who would die and others still who would come home with wounds they would carry for the rest of their lives.

“Oh God. This land only perseveres on the sacrifice of others. May God have mercy on Lord Autumn, as he continues to burden himself with sin…”

He prayed deliriously as the energy slowly drained from his head down, and soon he fell asleep right then and there. They retrieved the cask before it fell and placed it on a nearby shelf.

The way Reicher was slumped in the chair made it appear less like restful sleep and more like he had completely exhausted himself.

Col had Myuri fetch the assistant priest to ask what should be done, but he simply shrugged and told them to leave him be, that this was nothing unusual.

He could not bring himself to do that, but he knew all too well how difficult it was to carry a passed-out drunk. Then the assistant priest added peat to the furnace and draped a blanket over Reicher, so he would not be risk catching a cold.

Seeing that, they thanked the assistant priest and left the office.

Col wished to have a breath of fresh air, so they exited into the snowfall.

“Brother?”

As he reached the bottom of the steps, Myuri called out to him from the top.

“What is it?”

“Are you okay?”

Standing under the dim, snowy sky, Myuri’s silver hair looked like threads of ice.

“I’m all right.”

Then the expression on her face changed to that of slight surprise before she came down the steps.

“What is it?”

“I was just thinking how cool you’ve gotten. To think you were so sniveling just before that!”

He simply could not shake the somber expression from his face, which likely made him seem calm.

“It doesn’t matter how cool I am, but thanks to talking with you, I feel as though I’ve been able to steel myself.”

“Hmm?”

“Let’s bring Mr. Reicher along when we board the ship back to Atiph.”

Myuri was not surprised, but her rounded, reddish-amber eyes looked at him.

“He’s someone who can’t escape. I don’t really think we could convince him to, either.”

That was correct, and he understood how Reicher felt as well. Had Col himself come here alone and met Autumn, he would have surely ended up the same way.

“But luckily, he cannot hold his liquor as well as Ms. Holo.”

They would simply bring him on board after he passed out. He was not attached to this island—he was a prisoner of it. Once he left, chances were good that he would never come back.

Then Myuri widened her eyes at such a rough plan, and her lips slowly changed to that of a smile.

“Brother, that’s bad.”

“A true solution would be to find a way to make everyone on this island happy, though.”

“That doesn’t exist.”

She declared her conclusion without hesitation, even though she knew nothing about how big and complicated the world was.

That would be what a girl’s realistic intellect was.

“I cannot agree with that. But we lack the time and numbers to do so at the moment. So we can only think about what we can do right now.”

Myuri openly stared at him before suddenly looking away.

It was like a master who watched his apprentice finally grow to realize their full potential.

“Then can you reconsider this crazy ‘fix the world’ thing? And stop working with that blondie?”

“I have, for now, given up on sending my very young little sister home.”

“I’m only like your little sister!” She protested as she stomped her foot.

As they talked in the falling snow, whiteness covered their heads and shoulders before they knew it.

As Col brushed some off Myuri, he spoke.

“Why don’t we eat at the port for now?”

It seemed he had spent quite a long time having nightmares, and it must be noon around now.

Myuri squinted as he brushed the snow off, and with narrowed eyes, she opened her mouth.

“…Can I have meat?”

“Do you remember what Mr. Yosef said? The fish should be good here.”

“Then I want fried fish. With lots of salt on it!”

Though she seemed frail when her mouth was closed, her tastes were that of a drunk.

“Don’t eat too much.”

“Okay.”

It was their typical, clear-cut conversation, but there was something definitively different.

He was holding on to Myuri’s hand just a bit tighter than usual. She must have noticed as well.

In his hands was an extraordinarily precious jewel.

He had learned the depth of the darkness in the world, and now finally, he also knew the light.

Myuri sat dissatisfied at the table in the canteen because there was no fried fish to be had.

Towns and villages that did not butcher a number of

pigs every day could not keep a daily pot of fat. Herrings and sardines did give off some fat, but those who did heat them in a pan would likely not want to eat what was fried in it.

So in the end, she had a hodgepodge of fish stew, which was a bit of an exciting-looking dish for a girl raised in the mountains. The fish heads that floated in it, clearly a departure from the animals of the mountains, were mashed in half, their mouths crowded with eerie-looking teeth. It was only natural that even Myuri hesitated. However, once she started eating, she found that every bit of fish was delicious, and the soup had the perfect amount of saltiness for dipping bread. Her meal left her no room to concentrate on anything else.

The bread they ate was not made of wheat but of chestnuts. There was a peculiar hardness and harsh bitterness about it; this was not something one ate for fun. Col had not thought there was anything particularly luxurious about Nyohhira, but despite it being so snowy and deep in the mountains, the village was rich in food, likely due to its popularity as a place of healing, receiving its fair share of imports. He was once again made painfully aware of how blessed they had been.

“What are we going to do next, Brother?” Myuri inquired as she bit into a rather slim fish head, sharp teeth poking out from the corners of its mouth.

Her voice was low, maybe because she was busy biting the meat from the head, but it was more likely that it was her own way of being respectful in the quiet canteen.

“Preparations for a ship to go home…I would also like to investigate the island just a little more.”

“…You’re not giving up?”

When she looked at him with irritated eyes, he could not help but smile wryly.

“I do not think that saving the island is such an outrageous idea. I may be able to help somehow, and it may even be of benefit to Heir Hyland, as well.”

When she heard Hyland’s name, Myuri made the uninterested face she always did.

“By giving the island what they need, they may side with the Kingdom of Winfiel if war breaks out, even if not openly.”

“What about money? Isn’t that blondie rich?”

Myuri dunked her bread into the salty broth and bit into it.

“Money is powerful and will certainly help us. But it’s easy.”

“Easy?”

Her mouth was full of bread as she sloppily asked a follow-up question.

“Its appeal may as well be the same as violence. However, if we take the time to learn about the land and give the people what they truly need, they will understand our sincerity, even if it was worth the same amount of money. You see?”

Then she chewed loudly and swallowed with a glug. Myuri studied the rest of the bread, then nodded.

“I guess, if someone gave me my favorite kind of bread, I think I would do all I could for them.”

Though she typically preferred quantity over quality, it seemed the chestnut bread was not very good.

“So, in the meanwhile…”

She spoke vaguely up to that point and waved for him to come closer.

Col leaned over, wary that she may be planning some sort of trick, and she spoke to him.

“Can I look into who the little doll really was?”

Col stared back in surprise, but she was surprisingly serious.

“Mother won’t tell me the details, but she doesn’t know where her old friend that I’m named after and her other friends are, right?”

Myuri was implying that the Black-Mother may be one of them.

Myuri’s mother, the wisewolf Holo, once ruled over a forest in a land called Yoitsu, so it was hard to imagine that a much bigger wolf worked under her. There was a vague sense, though, that in the bygone age of spirits, size meant justice.

But knowing that this young girl was often bothered by the blood flowing through her and other nonhumans, his feelings were complicated. Though she seemed to not mind, at the end of the day that feigned indifference extended no further than the expression on her face.

“If the legend is a clue, then I have no idea why the fishing became really good after she stopped the lava.”

That was a good point. If the Black-Mother was not human, then what was she an avatar of?

“We’ll search for that together. It’s dangerous alone.”

Col sat back down in his seat.

“I’d be fine even if I came across a bear.”

“You may come across painful truths that are more frightening than any bear.”

He ripped off a piece of the chestnut bread and put it in his mouth. As he chewed quietly, Myuri sat across from him and stared off into space, perhaps deep in thought.

Then she suddenly looked back at him, and this time closed her eyes and tilted her head slightly, worried about something.

“What’s wrong?”

She groaned, answering as she furrowed her brows.

“Which do you like better—coddling me or being reduced to tears when a painful moment takes us by surprise?”

Col could not say he “liked” anything about the latter.

He looked at her in exasperation, and she suddenly opened her eyes in realization.

“Oh, you should just coddle me before and after something bad happens. That way, I’ll get the most out of it if you come with me.” She said with a satisfied smile.

“You should not be thinking in terms of profit.”

“Mother told me; she said that girls shan’t cry without accounting for it first.”

He was not sure if he would say he did not expect it from a mother and daughter of wolves, but she only seemed to be receiving precise instruction on the way of the hunt.

“I would prefer if you did not cry,” he said with a pained smile, when Myuri’s expression suddenly turned serious.

“The same goes for you.”

He could not believe a girl half his age said such a thing to him.

But simply because she was half his age did not mean that he was not happy to have someone worry about him.

“Thank you.”

He thanked her earnestly, and she looked at him dubiously for a while before grinning and returning to her food. He gazed at her for a while, and his mouth naturally began to smile.

It was often said to let one’s beloved child go on a journey, but when he looked at Myuri’s growth, he could only react with surprise. Or perhaps it was he who had not grown up, and he was only now realizing how amazing she was.

When a child became an adult, it was an important rite of passage to learn how wide the world was and how tall the sky was. If Col could learn the cold of ice and the depths of the sea, then perhaps he would grow more as a person as well. It was possible he could even find a different angle to look at his ideas for creating a new institution from the war between the Kingdom of Winfiel and the Church. Since faith took forms even he could not imagine, there was no single shape for the key to the gates of heaven. God’s house took many forms.

And he now knew that even the actions of nonhumans, like the one on this island, could help spread the teachings of God. Which meant the size of the gates needed to be made a bit larger as well.

He had been so shocked by Autumn that he had lost his head, but that, too, was a significant problem. To live among the world of humans, it was a problem they would have to seriously face one day. It seemed that Hyland had already realized the truth about Myuri and was vaguely aware that there were people like her throughout the world. Therefore, even in the smallest of possibilities, there was a chance that Caeson could become the precedent to open a new path.

Then, those like Myuri, who had stood before the world map at the trading house in Atiph, might not have to lament that there was no place in the world for them. There were many besides humans who possessed beautiful souls.

Col could not save the girl from being sold into slavery, nor could he offer any words of comfort to that lonely gaze of Autumn’s, who had no choice but to do what he did—but he could save Myuri.

When he reached that conclusio

n, something occurred to him.

“Myuri, I want to ask you something.”

“Hmm?”

Myuri sat satisfied before her bowl, which had turned into a boneyard, and she looked at him.

“Was Lord Autumn human?”

If the Black-Mother was not human, and the one who had spread her teachings was Autumn, then this possibility was the first thought that naturally came to mind.

But Myuri closed her eyes, as though searching her memory, and cocked her head.

“It was cold and my nose was a little stuffed, but I would have known if he smelled like beast. I could only smell the sea. It was like he hadn’t taken a bath for a really long time.”

Which meant Autumn was human.

Had he not been, though, then many things in his report to Hyland would have changed, and in the case that they did become enemies, she needed to know how disastrous that could be.

But it seemed well that he did not need to think about that.

“Are you full, by the way?”

“Yep. Thaaank you for the food.”

Then, with Myuri in tow, they walked around the port a bit.

It was a small town with no walls that could be crossed from one end to the other in a very short amount of time. Standing outside of town, the only thing to see once the buildings had disappeared were the snow paths extending in various directions, hardened by repeated footsteps. Their presence was only enough to guess that somewhere ahead there was a place where people gathered.

On the main street, there was a collection of buildings, a sign hanging from each of their eaves denoting different artisans, but it did not seem that they typically had goods out for display. Nor did it seem likely that any of these places were currently at work, as silence lay over them.

The only places open were a rope makers’ workshop that handled nets, and a blacksmith with a harpoon and a hatchet on display in the front. No matter what, it seemed that these two workshops were indispensable.

However, the net looked like something that had simply been re-braided whenever it became torn, while the bladed goods seemed more suitable for smashing instead of cutting. Without materials, craftsmen could not braid new rope, and without fuel, smiths likely could not refine their tools how they wanted.

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 2

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 2 Wolf & Parchment, Volume 3

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 3 Spring Log II

Spring Log II Spring Log IV

Spring Log IV Wolf & Parchment: New Theory Spice & Wolf, Vol. 4

Wolf & Parchment: New Theory Spice & Wolf, Vol. 4 Spring Log III

Spring Log III Spice & Wolf IV

Spice & Wolf IV Spice & Wolf X (DWT)

Spice & Wolf X (DWT) Spice and Wolf Vol. 2

Spice and Wolf Vol. 2 Spice & Wolf XIII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XIII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 10

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 10 Spice & Wolf XVI (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XVI (DWT) Town of Strife I

Town of Strife I Spice and Wolf, Vol. 5

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 5 Side Colors II

Side Colors II Wolf & Parchment, Volume 1

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 1 Spice & Wolf Omnibus

Spice & Wolf Omnibus Spice & Wolf XII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XII (DWT) spice & wolf v3

spice & wolf v3 Spice & Wolf

Spice & Wolf Spice & Wolf VIII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf VIII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 4

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 4 Spice & Wolf XIV (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XIV (DWT) Spring Log

Spring Log Spice & Wolf III

Spice & Wolf III Spice & Wolf VII - Side Colors

Spice & Wolf VII - Side Colors Spice & Wolf XV (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XV (DWT) Side Colors

Side Colors Side Colors III

Side Colors III Spice & Wolf VI

Spice & Wolf VI Spice & Wolf IX (DWT)

Spice & Wolf IX (DWT) Spice & Wolf V

Spice & Wolf V Town of Strife II

Town of Strife II Spice & Wolf XI (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XI (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 12

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 12 Spice and Wolf, Vol. 3

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 3 Spice and Wolf, Vol. 1

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 1 Spice & Wolf XVII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XVII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 6

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 6 Spice & Wolf II

Spice & Wolf II