- Home

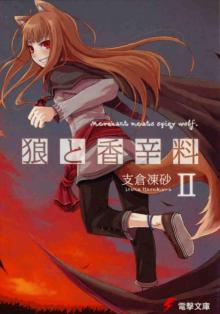

- Isuna Hasekura

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 5 Page 10

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 5 Read online

Page 10

Such a dish was a rare pleasure—an entire pig, spit down the center and roasted slowly over an open flame, occasionally drizzled with nut oil squeezed from a certain fruit.

Once the piglet was golden brown, its mouth was stuffed with herbs and it was served on a giant plate. It was customary for whoever cut off the piglet’s right ear to wish for good luck.

Normally such a dish would feed five or six people; it was generally ordered for celebrations of one kind or another, and when Lawrence gave his request to the barmaid, her surprise was obvious. A murmur of envy was audible among the other men in the tavern when the dish was brought out.

And when that same dish was set down directly in front of Holo, the voices became a sigh of sympathy.

It was not uncommon for Lawrence to weather envious gazes because of his beautiful companion, but these men seemed mollified once they understood that his existence was an expensive one indeed.

Seeing that Holo would be unable to carve the roast herself, Lawrence took it upon himself to do so, but he lacked the willpower to put any of the meat on his own plate, instead settling for the crunchy skin. The fragrant nut oil was tasty enough, but Holo beat him to the crunchy left ear. Wine went better with meat than ale, and it commanded a fair price.

Holo literally devoured the meal, completely unconcerned when her chestnut hair slipped out from underneath her hood, becoming occasionally spattered with oil from the roast. She was the very image of a wolf taking its food.

In the end, she made short work of the piglet.

As she finished taking the meat from the last rib, a round of applause arose in the tavern.

But Holo took no notice of the noise.

She licked her fingers clean of oil, took a drink of wine, and burped grandly. Her actions were strangely dignified, and the drunken patrons of the tavern sighed with their awe.

Still ignoring them, Holo smiled sweetly at Lawrence, who sat on the other side of the now-ravaged piglet carcass.

Perhaps she was saying thanks for the meal, but having reduced the piglet to bones, she seemed even keener to hunt.

Or perhaps it would serve as emergency rations for the next time she was hungry, Lawrence told himself when he thought of the truly painful bill, giving up all hope of escaping from Holo’s fangs. He would have no choice but to try not to forget about this emergency boon he had left buried in the den.

They rested for a while, and after Lawrence paid the bill—ten days’ worth of bribery surely—they left the tavern.

Perhaps being the center of the fur trade gave Lenos an excess of tallow. The road back to the inn was dotted with a number of lamps, which softly lit the way.

In contrast to the bustle of daylight, people walked in small groups, speaking in low tones as if trying not to blow out the flickering lamps.

Holo had a dreamy smile on her face as she walked, perhaps thanks to the satisfaction that came with demolishing the roast.

Lawrence held her hand to keep her from straying off the path.

“…”

“Hmm?” Lawrence intoned. It had seemed like Holo was about to say something, but she merely shook her head.

“’Tis a good evening, is all,” said Holo, looking vaguely down at the ground.

Lawrence, of course, agreed. “Still, we’d soon turn rotten if we spent every evening thus.”

A week of such indulgence would empty his coin purse and turn his brains to mush, no doubt.

Holo seemed to agree.

She chuckled quietly.

“’Tis saltwater, after all.”

“Hmm?”

“Sweet saltwater…”

Was she drunk, or was she trying to snare him yet again? Lawrence considered a reply, but the mood was too lovely to spoil with boorish chatter. He said nothing, and at length they arrived at the inn.

No matter how drunk they are, town dwellers can always find their way home as long as they can walk, but it is a bit different for travelers. No matter how tired their feet, they can persevere until they reach their inn.

Holo seemed to collapse as soon as Lawrence opened the door to the inn’s entryway.

No, Lawrence thought, she’s probably just feigning sleep.

“Goodness. At any other inn, you’d be scolded by the innkeeper,” came Eve’s hoarse voice. She and Arold were huddled around the charcoal hearth, Eve’s head covered as usual.

“Only on the first night. After that, they’d give us a hearty laugh, no doubt.”

“She drinks that much?”

“As you can see.”

Eve chuckled voicelessly and sipped her wine.

Lawrence passed the two of them, staying next to Holo in order to support her, when Arold—who had been reclining in his chair, eyes closed and apparently sleeping—spoke up.

“About that fur merchant from the north. I talked with him. Said the snow’s light this year, good conditions for travel.”

“I appreciate your asking.”

“If you want to know more…I forgot to ask his name again.”

“It’s Kolka Kuus,” offered Eve.

Murmured Arold, “Ah yes, that was his name.”

Lawrence would have liked to stay longer in this relaxed atmosphere.

“That Kuus fellow is staying on the fourth floor. He said he was mostly free in the evenings, so if you want to know more, go ahead and stop by his room.”

Everything was going extremely well.

But Holo pulled on his sleeve as if to hurry him, so Lawrence paid his thanks to Arold and took his leave, and the two began to ascend the stairs. Just as they did, Lawrence caught a glimpse of Eve raising a wine cup to him, as if to say, “Hurry back down.”

Step by step, they climbed the staircase, finally arriving at their room and opening the door.

How many times had Lawrence half carried Holo back to a room like this?

Before he met Holo, he had drunk and celebrated any number of times, but he always returned to his inn room alone, where the fear lurked that shocked the intoxication and joy from him.

Yet the fear was not gone.

It had merely been replaced with a new fear, as he wondered how many times he would be able to do this with her.

Though he knew it to be impossible, there was no escaping how much he wanted to tell Holo the truth—that he wanted to continue traveling with her forever. He now felt that whatever shape it took, being with her was his dearest wish.

Smiling ruefully to himself, Lawrence turned down the blanket and had Holo sit on the bed. He had gotten so that he could tell when she wasn’t feigning sleep.

He unwrapped her cape and removed her robe, took her coat off, and helped her out of her shoes and sash—all with such skill it was almost sad. He then laid her down on the bed.

She slept so deeply he didn’t think she would notice if he was to fall upon her.

“…”

The wine helped such notions bubble up in his mind, but he suddenly remembered Holo’s shamelessness. She really wouldn’t notice, right up until the end.

There is nothing so futile as all this, he thought, wilting faster than a popping bubble.

“You’re awful,” Lawrence murmured to himself, blaming her for his own selfishness, when she surprised him by moving, drawing herself up a bit.

Holo opened her eyes and gradually focused on him.

“What’s wrong?” Lawrence asked, alarmed at the sudden thought that she might be feeling sick.

But that didn’t seem to be the case.

From beneath the blanket, Holo reached her hand out.

He took it without thinking. Her grip was weak.

“…”

“Huh?”

“…Scared,” said Holo, closing her eyes.

He wondered if she had been having a bad dream. When she opened her eyes again, her face was tinged with a lingering embarrassment, as though she’d said too much.

“What could you possibly have to be afraid of?” asked Lawrence in a cheery

tone, and he thought he saw a grateful smile flicker on her face for a moment. “Everything’s going well right now, is it not? We have the books. We haven’t gotten swept up in any trouble. The path to the northlands is unseasonably clear. And”—he held her hand up for a moment, then lowered it—“we have yet to quarrel.”

This seemed to work.

Holo smiled, then closed her eyes again and sighed softly.

“You dunce…”

She snatched her hand away and wrapped herself up in the blanket.

There was only one thing Holo was afraid of.

Loneliness.

So was it the end of the journey that she feared? Lawrence himself feared it, and if that was the case, perhaps their travel proceeded too smoothly.

But even so, that didn’t quite seem to fit the expression on her face right now.

Holo did not open her eyes for some time. Just when Lawrence began to wonder if she was asleep, her ears twitched as if she anticipated something, and she stuck her chin out a bit. “…What I’m afraid of, it is…,” she began, then lowered her head when Lawrence reached out to caress it. “This is what I fear.”

“Huh?”

“Do you not understand?” Holo opened her eyes and looked at Lawrence.

Her eyes shone, not with scorn or anger but with terror.

Whatever it was, she truly feared it.

But Lawrence could not for the life of him imagine what that was. “I don’t. Unless…are you afraid of the end of our travels?” Lawrence managed to ask, though it took all his strength to do so.

Holo’s expression softened somehow. “That is, of course…frightening, yes. This has been the most fun I have had in a great while. But there is something I fear still more…”

She suddenly seemed very distant.

“’Tis well if you don’t understand. No”—she said, pulling her hand out from underneath the blanket and clasping the hand with which Lawrence still stroked her head—“even more than that, ’twould be troublesome if you did.”

She then laughed at some jest, covering her face with both hands.

Strangely, Lawrence did not feel like this was a rejection.

It rather seemed to be the opposite.

Holo curled up into a ball beneath the blanket, seeming this time to truly intend on sleeping.

—But then she popped her head out again, as though suddenly remembering something. “I do not mind if you go downstairs, so long as you do nothing to make me jealous.”

She had either noticed Eve’s gesture or was simply luring him into a trap.

In either case, she was correct about his plans. Lawrence patted her head lightly before answering. “Apparently I have a soft spot for jealous, self-loathing girls.”

Holo smiled, flashing her fangs. “I shall sleep now,” she said, then dove again beneath the blanket.

Lawrence still didn’t know what she feared.

But he wanted to allay that fear if he could.

He gazed at the palm of his hand, the sensation of her head beneath it was still palpable. He closed it lightly, as if to prevent it from disappearing.

He wanted to stay longer, but he needed to go and thank Eve for introducing him to Rigolo.

She was a merchant who might well be gone from the town tomorrow, depending on circumstances, and he didn’t want Eve to think of him as the kind of man who would tend to his companion before expressing proper gratitude.

After all, Lawrence himself had been a merchant for nearly half his life.

“I’ll be downstairs, then,” he murmured by way of some sort of excuse.

It occurred to Lawrence that what he’d told the barmaid earlier was true—that while he controlled the strings of his coin purse, his reins were tightly held. Frustratingly, he expected that fact was all too apparent from Holo’s perspective.

“…”

Yes, all he feared was the end of the journey.

But what did Holo fear?

Lawrence was lost in thought like a little boy.

Lawrence saw three inn patrons drinking on the second floor. One of them seemed like a merchant; the other two were probably itinerant craftsmen. If they had all been merchants, it was unlikely they would have been able to drink together so quietly, so Lawrence was confident in his guess.

He reached the first floor. Arold and Eve were still there.

It was almost as if time had stopped. Nothing had changed since he went upstairs. The two of them did not speak and stared in different directions.

“Did a witch sneeze?” Lawrence asked. It was a common superstition that a witch’s sneeze could stop time.

Arold only looked in Lawrence’s direction with his deep-set eyes.

If Eve hadn’t laughed, he would have worried he’d made some kind of faux pas.

“I’m a merchant, but not so the old man. Hard to make conversation,” said Eve.

Perhaps because there was nothing that served as a proper chair, she gestured at an empty wooden box.

“I was able to meet with Rigolo thanks to you. He certainly was a melancholy sort,” said Lawrence, taking the cup of wine Arold offered him. Someone could tell the stoic old man that his beloved daughter had come, and he probably wouldn’t even go out to meet her.

Eve laughed. “He is, isn’t he! There’s no helping a man that gloomy.”

“I do envy that technique of his, though.”

“So you saw that?” Eve said with a smile. “He likes you. If you could get him to help you with business, you’d be able to strip most merchants naked, don’t you think?”

“Unfortunately, he didn’t seem inclined.”

Rigolo was entirely indifferent to such things.

“That’s because he’s got everything he could ever want in that run-down, old place of his. You saw the garden, right?”

“It was incredible. You hardly ever see glass windows that large.”

Eve’s face was tilted down, but she looked up a bit and grinned at Lawrence’s purposefully merchantlike answer. “I’d never be able to handle such a life. I’d go mad, I tell you.”

Even if Lawrence didn’t feel as strongly about this, he understood Eve’s sentiment.

Merchants thought of profit roughly as often as they breathed.

“So did you hear about the meeting?” Eve’s eyes peered out from beneath her cowl. Arold turned an openly baleful gaze upon her. She looked away.

Lawrence wore a smile, but beneath that, his merchant’s face was ready.

“Apparently it’s finished,” he said.

Of course, Eve had no way of knowing whether or not that was true; she probably half doubted his answer.

That was assuming she didn’t have any background information. If she did, this new revelation might well tell her all sorts of things.

“And its conclusion?” she asked.

“Unfortunately, we didn’t get that far.”

Eve looked closely at him from beneath her cowl, like a child staring at an hourglass waiting for it to run out, but presently she seemed to decide that no amount of gazing would reveal any more information.

She looked away, sipping her wine.

It was time to go on the offensive.

“Have you heard anything yourself, Eve?”

“Me? Ha! No, he’s completely suspicious of me. Still, whether or not I believe you…hmm. Did those words really come out of his mouth?”

“It may well be the truth,” said Lawrence.

If a conclusion had indeed been reached, then there might be others who knew what it was and whose lips would be looser. If the meeting’s conclusion wasn’t something that would profit foreign merchants, then no one would be harmed by its telling.

In the first place, official town meetings were held based on the assumption that their contents would be made public.

“What worries, me, though…,” started Lawrence.

“Mm?” Eve folded her arms and looked in his direction.

“…is why exactly you are p

ursuing this avenue of conversation in the first place, Eve.”

Lawrence thought Arold might have smiled.

In a conversation between merchants, the interests and motivations of the participants were obscure, indistinct.

“You certainly get right to the point. Either you’ve done more than piddling two-copper business somewhere along the line, or you didn’t come to do a proper negotiation.”

It was hard to imagine a woman having such steady resolve.

No, to be a woman and a merchant, she would have to have that resolve.

“I’m like the rest,” said Eve. “I want to know how I can turn this into a huge gain. That’s all. What else would there be?”

“You could be trying to avoid a huge loss.”

Lawrence remembered the Ruvinheigen incident.

Even if one understood such loss intellectually, it was impossible to truly imagine until one experienced it for him or herself.

“People have two eyes, but it’s no mean feat to watch two things at once. Though I suppose from a certain perspective, you’re right about trying to avoid a loss.”

“By which you mean…?” asked Lawrence. Eve scratched her head at this.

Arold watched them, smiling beneath his bushy beard. The two were like longtime boon companions.

“I trade in stone statues.”

“Of the Holy Mother?”

The statue in Rigolo’s house flashed through Lawrence’s mind.

“Didn’t you see the one in Rigolo’s place? It’s from a port town called Gerube on the western seacoast. I buy them there and sell them at the church here. That was my business. Since it just amounts to transporting and selling stone, there’s not much profit in it, but if you can get one blessed by the Church, it’ll sell for far more. The pagans are stronger in this region, so when the northern campaign comes through, it brings throngs of people who want to buy statues.”

It was the strange alchemy of the Church. Just like in Kumersun, where speculation and enthusiasm drove the price of iron pyrite sky-high, religious faith could easily be turned into cash.

It was enough to make Lawrence want to have a go at it.

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 2

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 2 Wolf & Parchment, Volume 3

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 3 Spring Log II

Spring Log II Spring Log IV

Spring Log IV Wolf & Parchment: New Theory Spice & Wolf, Vol. 4

Wolf & Parchment: New Theory Spice & Wolf, Vol. 4 Spring Log III

Spring Log III Spice & Wolf IV

Spice & Wolf IV Spice & Wolf X (DWT)

Spice & Wolf X (DWT) Spice and Wolf Vol. 2

Spice and Wolf Vol. 2 Spice & Wolf XIII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XIII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 10

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 10 Spice & Wolf XVI (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XVI (DWT) Town of Strife I

Town of Strife I Spice and Wolf, Vol. 5

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 5 Side Colors II

Side Colors II Wolf & Parchment, Volume 1

Wolf & Parchment, Volume 1 Spice & Wolf Omnibus

Spice & Wolf Omnibus Spice & Wolf XII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XII (DWT) spice & wolf v3

spice & wolf v3 Spice & Wolf

Spice & Wolf Spice & Wolf VIII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf VIII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 4

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 4 Spice & Wolf XIV (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XIV (DWT) Spring Log

Spring Log Spice & Wolf III

Spice & Wolf III Spice & Wolf VII - Side Colors

Spice & Wolf VII - Side Colors Spice & Wolf XV (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XV (DWT) Side Colors

Side Colors Side Colors III

Side Colors III Spice & Wolf VI

Spice & Wolf VI Spice & Wolf IX (DWT)

Spice & Wolf IX (DWT) Spice & Wolf V

Spice & Wolf V Town of Strife II

Town of Strife II Spice & Wolf XI (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XI (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 12

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 12 Spice and Wolf, Vol. 3

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 3 Spice and Wolf, Vol. 1

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 1 Spice & Wolf XVII (DWT)

Spice & Wolf XVII (DWT) Spice and Wolf, Vol. 6

Spice and Wolf, Vol. 6 Spice & Wolf II

Spice & Wolf II